InfluxDB: building your own clustering

How to build your own clustered InfluxDB using Kafka

A while ago I published a short Twitter thread explaining a few of the problems I had run into while running their [enterprise] clustering solution; it’s been quite a painful process and I would like to write down the alternative architecture I ended up with while looking for improvements.

The original scenario

The original scenario I was working at was composed of a cluster of Go API servers backed by an InfluxDB database. Original service requirements demanded to deploy a fault-tolerant datastore so that’s the reason an InfluxDB cluster was put in place.

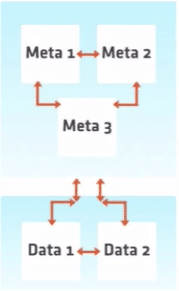

A general overview of our current deployment architecture is depicted below:

This clustering solution has 2 different parts:

- Control Plane: This comprises 3 meta nodes that implement the Raft protocol and make sure that all the cluster metadata information is consistent. This control plane provides the ability to add/remove nodes from the cluster, move shards around among many other different things.

- Data Plane: This part of the system comprises 2 data nodes and contains the data itself. These nodes are responsible for handling both write and read queries.

The problems

The clustering solution described in the previous section is not included in the Influx OSS version so that’s the reason the client had purchased a commercial license which allowed us to deploy:

- A three-node control plane. This is not a real limitation of the license; we could deploy more meta nodes in case we needed it.

- A two-node data plane. Here, with the existing licenses, we can only deploy 2 data nodes where each of them had 8 cores.

The aforementioned licensing model imposed us a set of restrictions which, basically, didn’t allow us to “easily” scale [up or out] the existing cluster. I had to go through the whole license negotiation cycle at $client: get the budget, talk to a few different departments, make sure everyone was on the same page,… Of course, this has nothing to do with the Influx database tech not even with InfluxData, the company selling the clustering capabilities, but I wanted to put on top of the table all the different factors that influenced the set of changes described later.

The previous reasons were not the only ones, of course; from a mere technical perspective a few different problems arose:

-

At the very beginning, before the movement towards their TSI index approach, the database process was restarted twice-thrice a day due to the high memory pressure created by their in-memory inverted index implementation.

-

The performance on the read side was annoying: +2 minutes for queries running through an hour of data grouping 2-3 different tags, long GC times while the previous queries were executed, …

-

The Hinted Handoff mechanism could bring the whole cluster down in a few minutes.

-

The anti-entropy service was a complete nightmare: it was enabled by default and it detected inconsistencies every time it was run, creating tons of pressure in the IO subsystem (and never correcting them).

-

The support service was unexpectedly bad: a long time to get a response back, a complete lack of knowledge about the systems they were supposed to be supporting. Sadly I had to go through the source code quite a few times, looking for explanations (for the commercial part the source wasn’t available so dealing with some of the aforementioned problems was even more complicated).

Taking into account all the previous considerations and the new set of changes (we’ll talk about them later on) that were about to be put in place into the whole system, I did consider that the price we were paying for this was not worth at all.

We were introducing Kafka as the backbone of our system so, why don’t take advantage of it and try to solve the clustering problem using a different approach?

A different approach: a write-ahead log (WAL) based on Kafka

A write-ahead log (WAL) is a very common practice used in many databases, including time-series databases. Very briefly, a WAL is an append-only file where the different actions that need to be performed in the database are persisted. Two of the most important advantages that a WAL provides are:

- Durability. Persisting actions in a WAL ensures that those actions will be exected even if the database crashes. Logging the actions before making changes to the different in-memory data structures implies that actions could be recorded and reapplied.

- Atomicity. If a server crashes midway executing various actions, the database can look at the WAL to find where it left off and finish the job.

Some drawbacks of the WAL approach are:

- Multitenancy. Since the WAL is running in-process we are limited to the amount of memory available in the system, making it harder to build a proper multi-tenant solution.

- Durability. There is no replication, so, if a disk dies, we lose the data.

Trying to solve the aforementioned shortcomings and to provide the right mechanisms to horizontally scale our existing cluster, the proposal was to use Kafka as a distributed WAL.

The requirements

The set of requirements we were trying to satisfy were:

- Multi-tenant. Properly handling of multiple tenants.

- Elasticity. The storage tier is horizontally scalable.

- Integrity. Data integrity should be preserved even in the presence of failures.

- Tolerant. It should be easy to replace nodes within the storage tier when it was needed (failure, deployment, etc).

The architectural basis

The architecture is based on a fault-tolerant cluster built using Apache Kafka (because it was already a part of the overall system). A high-level overview of the new proposed architecture is depicted below:

In this new proposed architecture, Kafka performs the function of a highly reliable and highly efficient WAL buffer for persisting time-series records that will be finally persisted into an InfluxDB instance(s).

Points will be written to a Kafka topic and this topic will replicate the data 3 times. Therefore, the loss of one Kafka broker node does not result in the loss of the topic’s data.

The Influx Relay implementation will read data from the aforementioned topic and will push the data into the InfluxDB nodes.

The load balancing layer is shown as a separate layer but it could be implemented in the consumer itself (in this case the previous Go endpoints are the only InfluxDB consumers) or just using an external load balancer (the current solution use an elastic load balancer provided by AWS).

The upcoming sections will go deeper into the details of the previous components.

Influx Relay implementation

The major responsibility of this new component is to read the data points from the Kafka topic and insert them into the InfluxDB node. It’s important to guarantee that:

- The data points are replicated across all the InfluxDB nodes in the cluster.

- Data retrieved from the Kafka partition is batched before it’s inserted into an Influx node in order to maximize the write-throughput.

An Influx-Relay instance needs to be deployed for every Influx node in the cluster. Every Influx-Relay instance will use its own Kafka consumer group, so, for example, if we want to deploy a 2 nodes Influx cluster (influx-node-0 and influx-node-1) we will need to deploy:

influx-relay-0process using theinflux-node-0-consumer-group.influx-relay-1process using theinflux-node-1-consumer-group.

This new solution ensures that the data will be eventually stored in all the Influx nodes. This means that, at some point in time, different nodes will potentially return different results depending on how far behind the node’s Influx-Relay counterpart is; this is totally acceptable due to the nature of the system we are building and it makes no difference with our current approach (our existing InfluxDB clustering approach would allow us to change this and provide stronger consistency at the expense of increasing the latency).

Failure scenarios

In the case of an Influx node failure, the other nodes will continue working independently and the data will continue to be delivered to them. Once the node is recovered, it will need to catch up in order to synchronize with the rest of the cluster nodes.

The synchronization protocol taking care of this process is something like the following one:

- When a node goes down it’s removed (manually or automatically) from the load balancing layer, making it unavailable for the consumers.

- Once the problem is fixed the

influx-relayprocess will, eventually, catch up with the rest of the members of the cluster - At the time the synchronization is done and the node is up to date we could add it back to the load balancing layer, and make it available to the query side of the system.

In a catastrophic scenario were, for example, a complete InfluxDB node is lost we can rsync the contents from an existing node and, after it’s done, start replaying from Kafka.

Sharding

The solution proposed in the previous paragraphs described a single topic with all the metrics and a set of process (one per Influx node) storing the data.

One of the big benefits of the proposed architecture is that it allows us to scale based on data sharding, splitting our datasets into disjoint groups.

For example, one potential scenario would be to shard our data based on the accounts of the system, so, we would have:

- A new topic for the account we want to split.

- A new set of Influx nodes (at least two).

- A new set of

Influx-Relayprocesses that will read from the new topic and will store the data of this namespace in the new Influx cluster.

In the load balancing layer, we will need to make sure that the queries for this account are directed to the proper InfluxDB instances.

But using the accounts is non the only alternative we have; we could use different alternatives to split the data. As an example, let’s imagine we have a single account where the number of series is so huge that doesn’t fit into a single database (remember that all the nodes in the cluster are identical). We could use a hash function (whatever we consider) to map our data to different Kafka partitions and deploy a new pair of Influx data nodes an Influx-Relay processes for every potential partition.

Now, in the load balancing layer, we would need to implement the same sharding logic we have implemented at write time, so we can redirect the queries to the corresponding Influx nodes.

Limitations

One of the main limitations of this proposed architecture could be at the read side, with queries that need to touch different shards. In these scenarios, the load balancing layer would need to be much smarter than the alternative proposed here and, for a single query, determine the set of shards which needs to be retrieved, execute all the required queries and compose the result that needs to be sent back to the consumer.

And not only that, if you want your writes to be highly consistent this is not probably a solution for you (it could be evolved but it was out of the initial scope since it wasn’t required at all).

Conclusions

Disclaimer: I have already shared all the contents included in this post with a few of the Influx folks. This doesn’t pretend to be a rant about the InfluxDB company at all; just wanted to share with you, very briefly, my experience building and running this [alternative] clustering system in case it could be useful for anyone.

The proposed architecture solved the problem faced here from both a technical and non-technical perspective and it’s, by no means, a general solution. The fact that Kafka was already deployed into the overall system simplified this a lot, it’s not that we had to introduce and operate a new piece of software.

With this new alternative in place, the problem of scaling up or out has been simplified quite a bit and can be done in a few minutes (avoiding all the bureaucracy and related stuff at $company).

One extra benefit is the fact that this new solution reduces the number of elements we need to manage: there’s no need to set up and operate a separate control plane and there’s no need to worry about communications across the different data nodes.