InfluxDB storage subsystem: the TSM files

A short series around the InfluxDB storage subsystem and its most important components

During this entry, we are going through the TSM part of the InfluxDB storage engine: how the contents are organized in the disk, how they are compressed or how they are compacted. This is the second entry of the series about the InfluxDB storage engine started in the previous post .

TSM files structure

The TSM files are where Influx stores the real data; these files are read-only files and are memory-mapped. If you’re familiar with any database using an LSM Tree variant this concept is very similar to the SSTable concept.

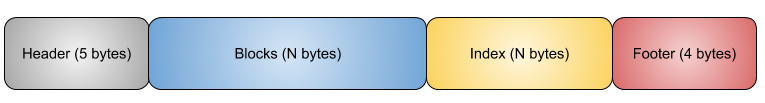

Let’s start with the structure of the files and how they are physically stored. At a high level, the structure is shown in the picture below:

The header

The header is a magic number which helps to identify the type of the file (4 bytes) and its version number (1 byte):

The blocks

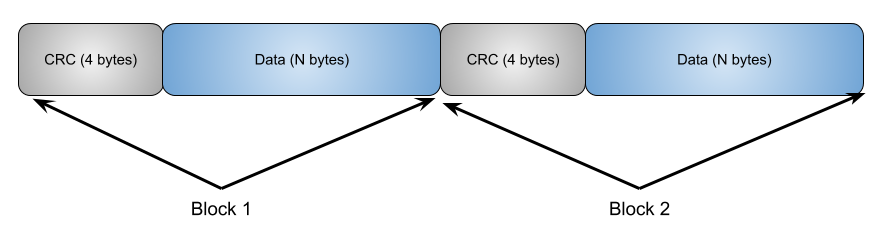

Blocks are sequences of pairs where every pair is composed of a CRC32 checksum and the data that needs to be stored. The diagram below shows how this part is structured:

The index

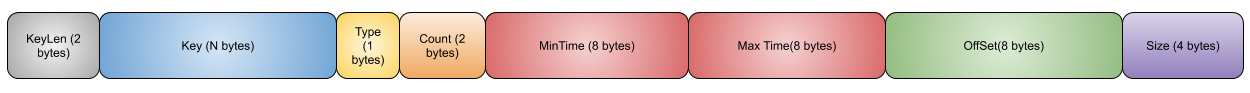

The index section serves, as its suggest, as the index to the set of blocks in the file and is composed of a sequence of entries lexicographically ordered by key first and then by time. The format of every entry in the previous sequence is shown in the next diagram:

- KeyLen: represents the length of the key.

- Key: represents the key itself.

- Type: represents the type of the field being stored (float, integer, string or bool).

- Count: represents the number of blocks in the file. For every block in the TSM file, there is a corresponding entry in the index with the following information:

- MinTime: minimum time stored in the block

- MaxTime: maximum time stored in the block

- Offset: the offset into the file where the block is located

- Size: the size of the block

Note how this index allows the database to efficiently access all the required blocks. When a key and a date are provided the database knows exactly which file contains the block and where this block is located and how much data needs to be read to retrieve the aforementioned block.

The footer

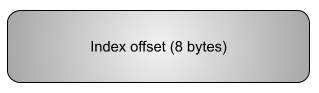

The last section of the TMS file is the footer that stores the offset where the index starts.

As we have already mentioned in the previous post, when the cache is full a snapshot is written to the corresponding TSM file:

// WriteSnapshot will snapshot the cache and write a new TSM file with its contents, releasing the snapshot when done.

func (e *Engine) WriteSnapshot() (err error) {

...

return e.writeSnapshotAndCommit(log, closedFiles, snapshot)

}

The previous snippet just highlights where the actual writing process is invoked; you can find more details here .

TSM File compression

Every data block is actually compressed before being persisted into the disk in order to reduce both IO operations and disk space. The structure of a block is shown below:

If you look carefully at the previous picture you can see that timestamps and the actual values are encoded separately, allowing the engine to use timestamp encoding for all the timestamps and the more appropriate encoding for every one of the fields. I think this has been a great decision and the usual compression ratios seem to validate this decision (I’ve seen compression ratios of 1:23, 1:24 in a few differente scenarios).

Complementing the timestamps and values encodings every block starts with a 1-byte-header where the four higher bits define the compression type and the four lower bits are there for the encoder in case it needs them. Right after this header, using a variable byte encoding mechanism, the length of the timestamps block is stored.

The compression mechanisms for every type of data are:

-

Timestamps: an adaptive approach based on the structure of the timestamps to be encoded is used. It’s a combination of delta encoding, scaling and compression using Simple8b run-length encoding (falling back to no compression in case it’s needed). You can find more details about this approach in the Gorrilla paper

-

Floats: I think, again, this encoding is based in the aforementioned Gorilla paper. If you’re interested to learn more about it, the paper has a nice explanation about its inner workings.

-

Integers: Two different strategies are used to compress integers depending on the range values of the data that needs to be compressed. As a first step, the values are encoded using Zig Zag encoding . If the value is smaller than

(1 << 60) - 1they are compressed the simple8b algorithm mentioned above and, if they are bigger, they are stored uncompressed. You can see where this decision is made in the next code snippet (extracted from here ):

if max > simple8b.MaxValue { // There is an encoded value that's too big to simple8b encode.

// Encode uncompressed.

sz := 1 + len(deltas)*8

if len(b) < sz && cap(b) >= sz {

b = b[:sz]

} else if len(b) < sz {

b = append(b, make([]byte, sz-len(b))...)

}

// 4 high bits of first byte store the encoding type for the block

b[0] = byte(intUncompressed) << 4

for i, v := range deltas {

binary.BigEndian.PutUint64(b[1+i*8:1+i*8+8], uint64(v))

}

return b[:sz], nil

}

- Booleans: they are encoded using a bit packing strategy (each boolean use 1 bit)

- Strings: they are encoded using Snappy

Compaction process

So far we’ve seen how all our points are physically stored in the disk and the reasoning behind the decision to use such data layout. Aiming to optimize the storage of the previous data from the query perspective, Influx continuously runs a compaction process. There’re a few different levels of compaction types

Snapshot

We’ve already talked briefly about this process; The values stored in the Cache and the WAL need to be stored in a TSM file in order to save both memory and disk space. If you remember for the previous post, we’ve already described this process in the previous post.

Leveled compactions

There are 4 different levels of compaction and they occur as the size of the TSM grows. Snapshots are compacted to level-1 files, level-1 files are compacted to level-2 files and so on. When level-4 is reached no further compaction is applied to these files.

Going deeper into the inner workings of the leveled compaction process would take a whole separate blog entry so I am going to stop here

Index optimization

In the scenario where many level-4 TSM files are created, the index becomes larger and the cost of accessing it increases. This optimization tries to split the series across different TSM files, sorting all points for a particular series into the same file.

Before this process, a TSM file stores points about most of the series and, after the optimization is executed, each of the new TSM files store a reduced number of series (with very little overlap among them).

Full compactions

This type of compaction process only runs when a shard has become cold for writes (no new writes are coming into it) or when a delete operation is executed on the shard. This compaction process applies all the techniques used in the leveled compactions and the index optimization process

Wrapping up

In this post, I’ve covered a few details about the TSM part of the InfluxDB’s storage engine, going a little bit deeper into some of the concepts introduced in the first post of this series.

In the next post, I will try to provide a few details about the TSI files and how this part of the storage subsystem helps Influx to speed up more complex queries.

Again, we’ve used InfluxDB as the vehicle to show some of the concepts used for building a database: how the information is organized in the disk, compression, efficiently looking for information, … Of course, this will be dependent on the type of database being built.

Thanks a lot for reading! I hope you have enjoyed it as much as I have done writing it.